Fragmentation has a bad reputation now.

People hear the word and immediately think of broken systems, slow machines, outdated hardware, or things you should avoid. That framing is wrong. Fragmentation isn’t failure. Unmanaged fragmentation is failure. There’s a difference, and modern tools blurred it so badly that people forgot how systems actually work.

I didn’t learn fragmentation from textbooks or best practices. I learned it the hard way: by breaking things, by editing files directly, by watching systems fail in predictable ways because I changed one part without understanding the rest.

That’s why this topic still matters.

Fragmentation Is How You Make Problems Small

At its core, fragmentation is simple. You break a system into parts so that when something fails, it doesn’t take everything with it.

That applies to storage, software, operating systems, testing, even learning itself.

Modern advice treats fragmentation as something to eliminate. In reality, good systems fragment aggressively, but intentionally.

When Defragging Was Actually PC Maintenance

Back in the 286, 386, 486 days, fragmentation wasn’t a concept you debated, it was a problem you managed.

Early DOS games were tiny. Pac-Man, Dig Dug, Galaga, Yahtzee, even strip poker. These games were small enough that you could fit multiple games on a single 1.44MB floppy disk, often under 100KB each. Many of them ran directly from the floppy without needing hard drive installation at all.

But as games evolved, that changed. By the time Doom came around in 1993, you needed about 20MB of hard drive space and the game came on multiple floppy disks. You couldn’t run it from a floppy anymore. You had to install it to your hard drive, and that’s when fragmentation from install/uninstall cycles became a real problem.

Hard drives back then had small capacities. 60 megabytes, 120 megabytes, 240 megabytes. A 520 megabyte drive was already impressive. When I got a 1 gigabyte drive, that changed everything. I could install over 100 games.

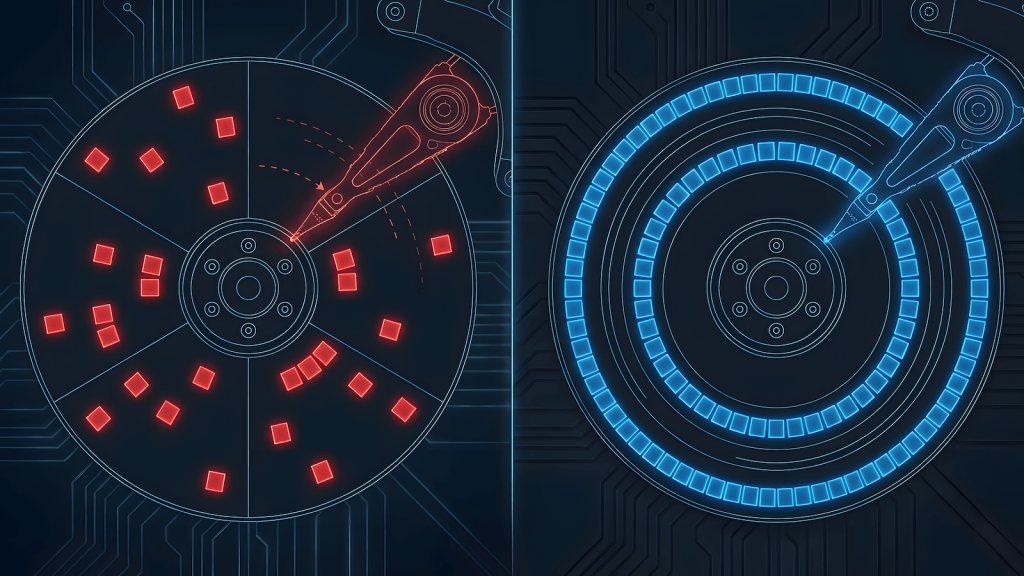

Install a few games, delete one, install another, repeat that cycle a dozen times, and your drive layout looked like chaos. Files didn’t stay in one clean location, they split across multiple physical areas on the disk. The read/write head had to jump around to piece together a single file. More fragmentation meant more seek time, and seek time meant slower performance.

Defragging wasn’t optional. It was mandatory PC maintenance.

You ran your defrag tool every few weeks because if you didn’t, your machine got noticeably slower. It wasn’t some enthusiast flex or optimization trick. It was basic upkeep, like changing oil in a car. That knowledge wasn’t optional. You learned to defrag because you had to.

The Shift From “Make It Work” to “Buy New”

Computers back then were expensive. Not just the initial purchase, expensive to upgrade. You bought a whole system, not modular parts. Sure, modular components existed, but they cost enough that most people couldn’t afford to just swap things out when performance degraded.

When your PC slowed down, you didn’t buy new hardware. You made it work.

That meant understanding what was happening under the hood. Most PC users back then knew how to fix their machines because they had to. Defragging was part of that basic literacy.

Now? Hardware is more accessible. Not cheaper necessarily, but available. Modular parts are everywhere. When something slows down, people buy new instead of tune. The knowledge got lost because the forcing function disappeared.

SSDs removed the mechanical fragmentation problem entirely. No moving read/write head, no seek time penalty, fragmentation doesn’t matter the same way. The automation worked so well that people stopped understanding why fragmentation existed in the first place.

Now defragging is either treated as “obsolete knowledge” or “enthusiast flexing.” But the concept didn’t disappear. It just got buried under layers of automation.

Hard Drives Are the Easiest Example, and the Most Misunderstood

“Don’t use hard drives.”

“SSDs are always better.”

“Cheap storage slows everything down.”

Those statements sound technical, but they’re lazy abstractions.

Here’s what actually matters: boot latency is sensitive, random access is sensitive, large static assets are not.

That’s why a system with OS on SSD and games and data on HDD works perfectly fine for many workloads.

Games don’t constantly rewrite themselves. They load assets, stream predictably, and then run mostly in memory. If the drive isn’t being thrashed by constant installs and deletes, fragmentation barely grows.

The problem isn’t HDDs. The problem is churn.

Fragmentation Comes From Churn, Not Capacity

Fragmentation increases when you install and uninstall repeatedly, overwrite large blocks, or reshuffle data constantly.

If you install once and leave files alone, the layout stabilizes. A defragmented hard drive with a stable workload behaves predictably and lasts a long time. That’s not nostalgia, that’s physics.

Modern operating systems hide this because they assume users don’t want to think about it. That’s fine, until the abstraction turns into misinformation.

Optimization Is Placement, Not Speed

People fixate on specs because they’re easy to compare. Engineers look at where things live.

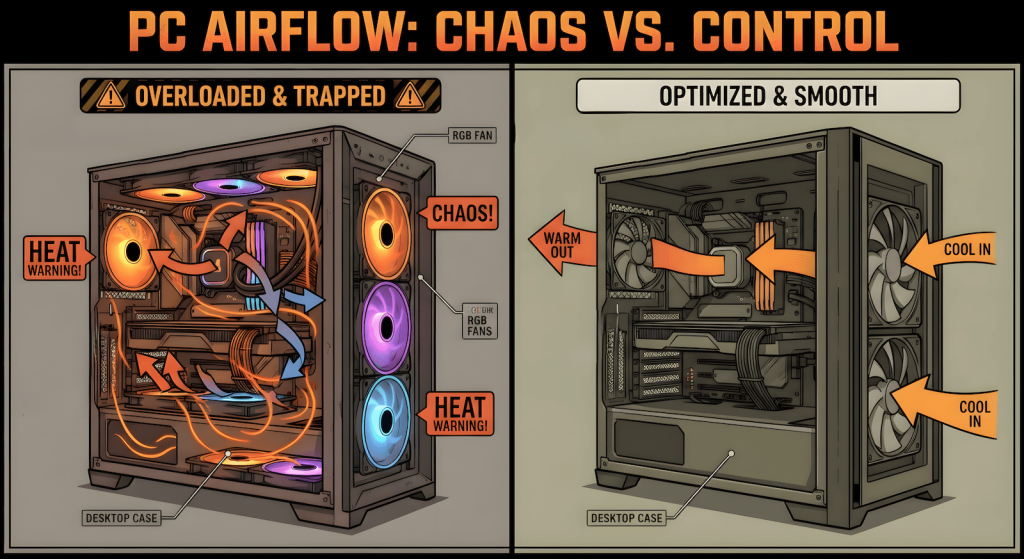

Fragmentation done right looks like this: SSD for things that need fast access, HDD for things that don’t, memory for what runs continuously, storage for what stays put.

That’s not settling, that’s design.

Lowering visual fidelity to maintain smooth gameplay follows the same logic. You don’t brute-force the system, you work within its constraints.

That mindset never stopped being relevant. Understanding placement from the old PC maintenance days is why you can still tune systems instead of replacing them.

Fragmentation Is Why Debugging Works

This idea extends beyond hardware.

You don’t test an entire system every time something changes. You isolate, you reduce scope, you narrow failure. That’s fragmentation.

When people ask AI to build entire systems in one shot, they run into the same problem: the model changes everything to fix one thing. Without fragmentation, causality disappears. You can’t tell what broke because everything moved.

Good systems make causality visible by keeping parts small.

Modern Tools Didn’t Remove Fragmentation, They Automated It

We didn’t eliminate fragmentation, we buried it under layers.

File systems still fragment. Memory still fragments. Software still fragments into services, modules, and dependencies. The difference is that modern tools manage it automatically, which is great, until the automation doesn’t match your workload.

When it doesn’t, people panic because they no longer understand what’s happening underneath.

That’s not progress, that’s lost literacy.

Why This Still Matters

Hard drives aren’t obsolete. SSDs aren’t magic. Abstraction isn’t evil.

What’s dangerous is pretending systems are simple when they’re not.

Fragmentation is how systems survive change. It’s how failures stay local. It’s how learning sticks.

If you’ve ever tuned a machine instead of replacing it, isolated a problem instead of brute-forcing it, or accepted limits instead of fighting physics, you already understand fragmentation, even if no one calls it that anymore.

The Point Isn’t Old Hardware

This isn’t about defending hard drives, it’s about defending thinking.

Fragmentation isn’t a flaw, it’s the reason complex systems don’t collapse under their own weight.

Ignore it, and you end up buying solutions you don’t need. Understand it, and you build systems that last.

Pingback: Why QA Fails Without Fragmentation (and How Fragmentation Protects Systems) - QAJourney