Conquest of Camelot is one of the hardest games I’ve ever played, and I still haven’t finished it.

Not because it’s broken.

Not because it’s unfair.

But because it does exactly what it says it will do.

Early on, the game makes a promise that most players gloss over: you will be tested in every way so you may remain worthy to possess the Grail. It doesn’t mean combat difficulty. It doesn’t mean puzzle density. It means mind, body, and spirit and the game never compromises on that idea.

That single sentence is why Camelot still matters, and why it’s closer to pen-and-paper RPGs than most modern games that claim the lineage.

This Is Not a Game That Handholds

It Barely Explains Itself

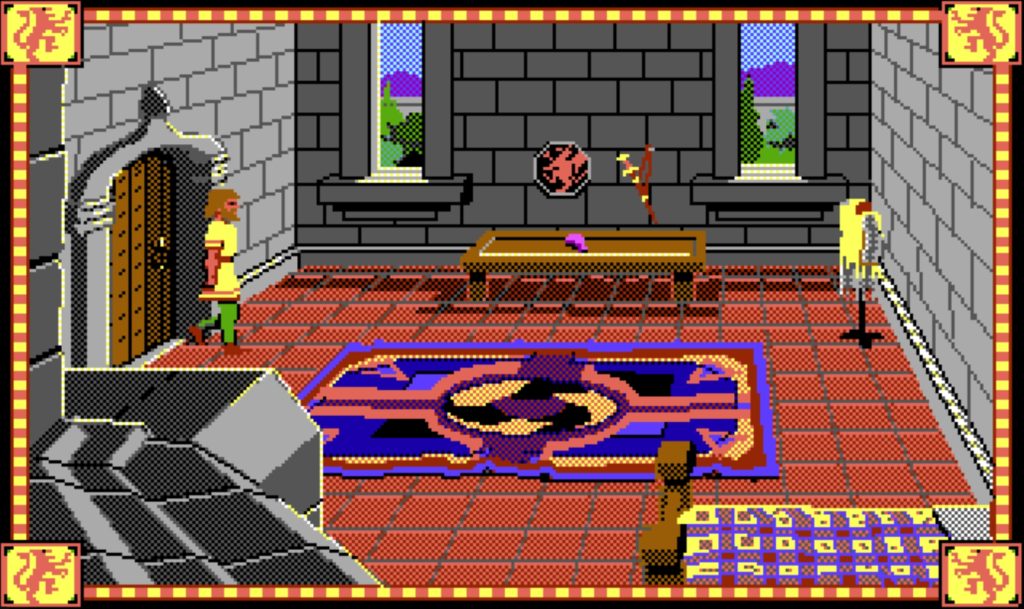

Conquest of Camelot does not teach through tutorials. It teaches through refusal.

You don’t “give copper.”

You give a purse, after you deliberately hand it to the treasurer, explicitly name gold, silver, and copper, then take it back. That sequence matters. It forces you to acknowledge what Arthur carries and why.

You don’t ask about the boar spear.

You notice it first. You look. You examine the hunter’s tools, the skins, the environment. Only then does the spear become a valid thing to talk about.

The parser isn’t being difficult.

It’s being literal.

Arthur can only act on what you have demonstrated awareness of.

Role-Playing Is About Arthur’s Awareness, Not Yours

This is the rule most people miss.

The game does not react to what you, the player, can see on the screen.

It reacts only to what Arthur has acknowledged.

If a spear is visible, that does not mean Arthur has seen it.

If an object is clearly drawn, that does not mean it exists in Arthur’s understanding of the world.

Nothing is assumed. Nothing is automatic.

Until you deliberately look, examine, or acknowledge something through action, it does not exist as part of Arthur’s reality. That’s why the hunter won’t talk about the boar spear until you explicitly notice it not because of missing dialogue flags, but because Arthur hasn’t demonstrated awareness yet.

The parser enforces that separation relentlessly.

You are not omniscient.

Arthur is not telepathic.

And the world will not bridge that gap for you.

The Game Lets You Continue While Already Failing

This is where Conquest of Camelot quietly breaks most players.

You begin with a horse and a donkey. In one early situation, if you failed to prepare properly specifically, if you didn’t secure the boar spear, you lose the horse.

The game does not stop.

There is no warning.

No reload prompt.

No “critical item lost” message.

You simply continue.

But now:

- You cannot kill the boar.

- One region becomes functionally unfinished.

- Later, you cannot joust the Black Knight.

Not because you’re weak.

Because you were unprepared hours ago.

The game doesn’t block progress.

It removes capability.

That distinction matters.

Brute Force Is Possible, but It’s a Lie

Yes, you can brute-force Conquest of Camelot.

You can save constantly, reload steps, memorize patterns, and push success probabilities from something like 2–3 percent upward.

But brute force only works locally.

Each region contains clues, context, and preparation for later trials. Miss those, and future areas don’t just get harder they become incomplete. You’re not stuck. You’re hollowed out.

That’s why the game feels “unfinished” when played like a system to beat. Narratively, it is unfinished. You didn’t earn what that part of the world was meant to give you.

Tested in Mind

The test of the mind isn’t intelligence. It’s discipline.

The game expects you to read carefully, remember details across regions, and connect events separated by time and geography.

There is no quest log.

No recap.

No reminder pointing back to your mistake.

If you lose context, the game doesn’t correct you. It waits.

Tested in Body

Physical trials exist, but they’re conditional.

Combat only works if you prepared correctly, paid attention earlier, and respected the world’s logic.

Strength in Camelot is earned upstream. By the time swords are drawn, the outcome was already decided by how you lived.

Tested in Spirit

The Grail Is a Judgment, Not a Reward

This is where most players quietly fail.

Mercy versus expedience.

Humility versus entitlement.

Patience versus shortcuts.

There is no morality meter.

No feedback.

No confirmation.

You can reach the end having “done everything” and still be denied the Grail.

Because the Grail is not a prize.

It’s a verdict.

Why This Is Real Role-Playing

In pen-and-paper RPGs, you don’t select dialogue options. You state intent. The dungeon master decides if it makes sense, and the world reacts accordingly.

That’s exactly how Conquest of Camelot works.

The parser is not a limitation.

It is the interface to intent.

If you are vague, Arthur is vague.

If you miss something, Arthur misses it.

If you act without awareness, the world does not adjust for you.

That’s tabletop DNA, not modern game convenience.

Why I Still Haven’t Finished It

I didn’t fail this game because I was a kid.

I failed because the game assumed adult attention, long-term accountability, and moral consistency without feedback. It let me continue while already unworthy.

I never reduced it to a checklist or a walkthrough just to see the ending.

That’s why it stayed unfinished not as a failure, but as an intact experience.

Playing It Today (Without Diluting It)

You can run Conquest of Camelot cleanly today using DOSBox. The goal isn’t convenience, it’s fidelity.

- DOSBox preserves the parser pacing and timing.

- Keyboard-driven input remains intact.

- No modern overlays dilute the interaction.

If you want a legal, friction-free copy, GOG is the safest source. It bundles the game with DOSBox preconfigured, while still letting you tweak settings if you want the experience as close to original hardware as possible.

No emulation circus. No abandonware roulette.

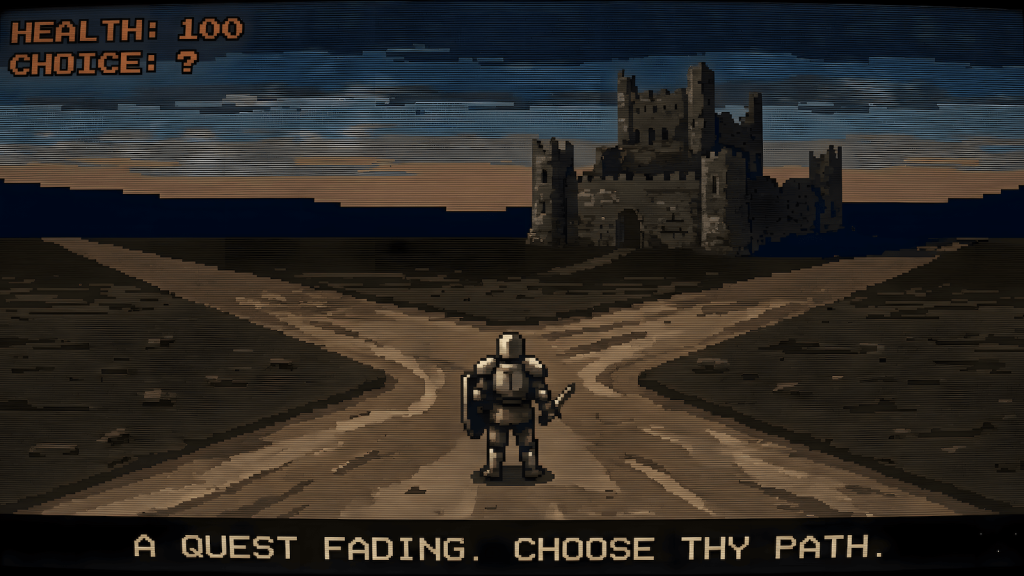

Why the Intro Matters

(and Why the Embedded Video Exists)

The game’s intro isn’t nostalgia bait. It’s a declaration.

It tells you before you touch the keyboard that this is about worthiness, not victory. That silence, pacing, and restraint are intentional.

That’s why the embedded video exists here. Not as a walkthrough. Not as content padding. As primary evidence.

Watch it, then read the post. Or read first, then watch. Either way, the contract is the same.

Why It Still Matters

Conquest of Camelot isn’t important because it’s old.

It’s important because it proves something modern RPGs often forget: real role-playing is about how you behave when the world refuses to explain itself.

Camelot doesn’t ask if you want to be Arthur.

It watches to see if you actually are.