Some links on this page are Amazon affiliate links. If you choose to buy through them, HobbyEngineered may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you.

These links only appear where tools or everyday support items naturally fit the topic. No sponsored placements. No hype.

Most people talking about Dune right now are talking about the movies. I’ve watched the David Lynch film and caught some of the newer Villeneuve versions, but honestly? The books are still what matter to me.

I’ve read all six of Frank Herbert’s original novels. I’ve read the prequels. I’ve spent years collecting these stories, hunting down physical copies, and living in this universe.

This isn’t a book review. This is about why these books became part of my collection and why they’re still worth the effort to find.

How I Found Dune Through the RTS Game

My entry into Dune wasn’t through the books. It was through Dune 2, the real-time strategy game from the early 90s.

I played that game obsessively. Every campaign. Every difficulty. All three factions: Atreides, Harkonnen, Ordos.

Each faction had its own tactical advantages:

- Harkonnen had raw power with devastators and heavy units that could crush bases

- Atreides had sonic tanks that could wreck entire armies

- Ordos had deviators, units that could convert enemy forces to your side

The game had balance. It had strategy. And it had a world that felt real even though I didn’t fully understand it yet.

I knew there was spice. I knew there were sandworms. I knew the factions were fighting over a desert planet. But I didn’t know the why behind any of it.

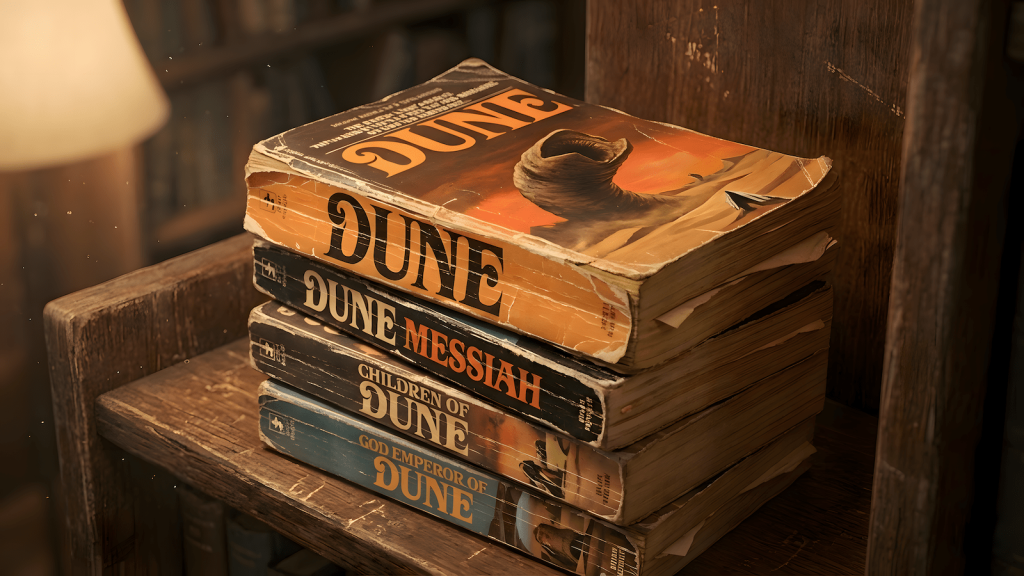

Then, years later in college, I saw Dune at Booksale.

Not just any edition. The 1977 Berkley edition. The one with the massive orange lettering, the sandworm, the desert landscape. “AN UNPARALLELED ACHIEVEMENT OF IMAGINATION” printed at the top.

I recognized the name from the game. I bought it immediately.

That book is gone now. I don’t know where it went. But before it disappeared, I read it. And then I couldn’t stop.

Why I Read All Six Books (Not Just the First)

Most people who say they’ve read Dune mean they read the first book. Some push through to Dune Messiah. A few make it to Children of Dune.

But the real story, the one Herbert intended, spans six books and over 5,000 years of in-universe history.

Here’s the journey:

The Rise and Fall of Paul Atreides

- Dune – The political maneuvering, the spice, the Fremen, the rise of Paul Muad’Dib

- Dune Messiah – Paul as Emperor, trapped by his own prescience, dealing with the jihad he unleashed

- Children of Dune – Paul’s children, Leto II and Ghanima. Leto begins his transformation into something no longer human

The God Emperor Era

- God Emperor of Dune – 3,500 years later. Leto II is now a sandworm-human hybrid ruling as an immortal tyrant. The book is philosophical, slow, dense. It reframes everything that came before

The Far Future

- Heretics of Dune – Thousands of years after Leto’s death. The Bene Gesserit are the dominant power, but a new threat emerges: the Honored Matres

- Chapterhouse: Dune – The Bene Gesserit versus the Honored Matres. Herbert’s final book. He died before finishing the series, so it ends on a cliffhanger

This isn’t just one story. It’s a chronicle of human evolution, power, survival, and the consequences of trying to control the future.

What Made Dune Worth Collecting

What makes Dune worth collecting isn’t just the story. It’s the world.

The Factions and Houses

The Imperium is held together by a delicate balance of power.

House Atreides. Noble, honorable, but politically vulnerable. Duke Leto and his son Paul are the protagonists, but they’re not traditional heroes.

House Harkonnen. Brutal, sadistic, ruled by Baron Vladimir Harkonnen. They control Arrakis before the Atreides arrive, and they’ll do anything to take it back.

House Corrino. The Emperor’s house. Shaddam IV plays the great houses against each other to maintain his throne.

Then there are the power brokers who operate beyond the feudal system.

The Bene Gesserit. A sisterhood with mental and physical control so advanced it seems superhuman. They’ve been running a breeding program for generations to create the Kwisatz Haderach, a male Bene Gesserit with the ability to access genetic memory and see all possible futures.

The Spacing Guild. They control all interstellar travel. Without the Guild Navigators who use spice to fold space, there is no empire.

The Fremen. The native people of Arrakis. Desert warriors who’ve adapted to the harshest environment in the universe. They’re more dangerous than even the Emperor’s Sardaukar because Arrakis forges them harder than any training world.

The Mark of Spice

One of the distinctive features of Arrakis is the “blue within blue” eyes. It’s not just a cosmetic detail. It’s a physical marker of spice addiction. Anyone who lives on Arrakis long enough, who breathes the spice-saturated air and consumes it in their food and water, develops these eyes. The Fremen all have them because they’ve spent their entire lives in the deep desert. Guild Navigators have them because they’re saturated in spice to enable space folding. It’s proof you’ve been changed by the planet.

The Characters That Kept Me Reading

Herbert understood something fundamental. Environment creates warriors.

The Sardaukar are the Emperor’s elite troops, trained on Salusa Secundus, a prison planet so brutal that only the strongest survive. They’re feared throughout the Imperium.

The Fremen are deadlier because Arrakis is harsher than Salusa Secundus. Water is so scarce they recycle moisture from their dead. Every drop is sacred. The desert doesn’t just train them. It shapes their entire culture and philosophy.

The Loyal Warriors of House Atreides

Duncan Idaho. Swordmaster of the Ginaz. In the book, Herbert describes him with curling black hair, a dark round face, and feline movements. He’s loyal to the core, dies protecting Paul, and gets resurrected as a ghola (Tleilaxu genetic copy) multiple times throughout the series.

When I read Duncan’s descriptions, I imagined someone tall and agile. A real swordmaster, the kind where one look tells you that fighting him would be your last mistake. Not a bulky barbarian. A duelist. Jason Momoa played him in the newer films, and while he brought the swashbuckling energy, he felt too massive for what I’d pictured. But that’s the thing about reading. Your version exists first.

Gurney Halleck. Warrior, troubadour, survivor. Escaped Harkonnen slavery and became one of Duke Leto’s most trusted commanders. In my mind, he always had that smuggler edge. Rough, skilled, dangerous. Patrick Stewart’s portrayal in the David Lynch film actually nailed it for me. That combination of weathered warrior and underlying nobility.

Thufir Hawat. Mentat and Master of Assassins. Herbert describes him as a grizzled elderly man with leathery skin, deeply seamed face, and lips stained cranberry-red from sapho juice, the drug mentats use to enhance their computational abilities. He’s old, weathered, with the look of someone who’s survived exotic battlefields.

When I read about Thufir, I thought of him like Alfred from Batman. Old, but you could tell he was still dangerous. Someone who could take you apart before you realized what happened. The newer films made him look more like a political advisor, which missed that edge for me.

The Harkonnens

Baron Vladimir Harkonnen. The grotesque, floating monster who rules through fear and cruelty. Herbert makes him physically repulsive on purpose. His evil is written into his body.

Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen. The Baron’s nephew and chosen heir. Dangerous, cunning, charismatic in a twisted way. Sting’s portrayal in the David Lynch film captured that perfectly for me. The right mix of menace and appeal.

The Women Who Shape Everything

Lady Jessica. Bene Gesserit concubine to Duke Leto, mother of Paul and Alia. She was ordered to bear a daughter for the breeding program but chose to give Leto a son. That choice set everything in motion.

Princess Irulan. Daughter of Emperor Shaddam IV, historian, and eventually Paul’s wife in title only. Virginia Madsen played her in the Lynch film, and Florence Pugh brought something interesting to the role in the newer version. Both worked for different reasons.

Chani. Fremen warrior, Paul’s true love, mother of his children. Here’s where my mental image diverged completely from every film adaptation.

In my mind, I always pictured Chani as red-haired, athletic, built like Lucy Lawless in Xena. That powerful, warrior-woman physique. Someone who looked like she could actually ride sandworms and lead raids. The kind of physical presence that would match Catwoman or Wonder Woman in terms of strength and grace.

The David Lynch film cast someone beautiful, but she didn’t match what I’d imagined. The newer films went in a completely different direction.

And that’s the thing about watching movies after reading. They replace your mental image with someone else’s interpretation. Suddenly the character you’ve been visualizing for years is gone, overwritten by an actor who doesn’t match. The small details from the books get changed or lost in adaptation, and your version, the one you built while reading, disappears.

That’s not about hating any particular actor. It’s about protecting what your imagination created. Once you see the movie version, you can’t unsee it. And sometimes, honestly, I’d rather keep my version intact.

Alia Atreides

And then there’s Alia. St. Alia of the Knife. Paul’s sister, born with full consciousness and access to ancestral memories because Lady Jessica took the Water of Life while pregnant. She’s a child with the mind of countless generations, wielding a crysknife with deadly precision.

Alia was one of my favorite characters in the first book. This small, terrifying figure who could see through Bene Gesserit deception and kill Baron Harkonnen herself with a poisoned needle. She was powerful, clear-sighted, dangerous.

By Dune Messiah and Children of Dune, watching her fall to Abomination, possessed by the Baron’s consciousness lurking in her genetic memory, was genuinely tragic. But I loved what she represented in that first book. Strength, prescience, someone who could see through lies and act decisively.

I loved the character enough that I named my daughter after her. Not for the tragedy that comes later, but for what she was at her best. Fearless, aware, powerful.

The Litany Against Fear and Bene Gesserit Powers

One of the most memorable elements of Dune is the Litany Against Fear, taught by the Bene Gesserit:

“I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration. I will face my fear. I will permit it to pass over me and through me. And when it has gone past I will turn the inner eye to see its path. Where the fear has gone there will be nothing. Only I will remain.”

It’s not just a quote. It’s a mental discipline technique.

The Litany doesn’t tell you to avoid fear or suppress it. It tells you to acknowledge it, experience it fully, and remain standing after it passes.

That principle stuck with me. Not in some performative way, but because it actually works when you’re anxious or facing something difficult. Let the fear run its course. Don’t fight it. Don’t run from it. Just let it pass through. Then move forward.

The Gom Jabbar Test (And Why I Felt the Pain)

Early in the first book, Paul faces the Gom Jabbar test administered by the Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam.

Here’s what actually happens. Paul places his hand in a box that creates the sensation of intense, escalating pain. Burning, like thousands of ants eating away at his hand. The Reverend Mother holds a poisoned needle (the Gom Jabbar) at his neck. If he withdraws his hand from the pain, she kills him instantly.

The test isn’t about pain tolerance. It’s about determining if you’re human or animal.

An animal reacts to pain instinctively. It pulls away to survive. A human can override that instinct through reasoning and willpower. The ability to endure suffering for a greater purpose, to control base survival reactions through conscious thought, that’s what separates human consciousness from animal reflex.

Paul keeps his hand in the box even as the pain intensifies. He believes his hand is being destroyed, that when he pulls it out, it will be nothing but a stump, completely gone. But he doesn’t remove it because he understands what’s at stake.

When I read that scene, I felt it. I mean physically felt it in my right hand. The phantom sensation of burning, the dread that my hand was being destroyed. I couldn’t move my hand while reading those pages. That’s the power of books and imagination. The pain wasn’t real, but my mind made it real enough.

Understanding Prescience While Reading

One thing I kept thinking about while reading was: what does prescience actually feel like?

Herbert describes it as seeing possible futures, branching paths that shift based on decisions made. For someone like Paul, who gains prescience through spice exposure and his Bene Gesserit heritage, it’s not just visions. It’s being trapped by what you see. He knows the jihad is coming. He knows millions will die in his name. But every path he sees leads there.

For me, reading it, I imagined prescience as something between foresight and a psychedelic experience. You take spice, you feel a headache or disorientation, and then suddenly you’re seeing what could happen. With training and mental discipline (like the Bene Gesserit have), you can control it, navigate through the visions. Without that training, it’s overwhelming. Too many futures, too much information.

Was Herbert implying it’s like a drug trip? Maybe. Spice is clearly psychoactive. But it’s also more than that. It’s expanding consciousness to perceive time differently. That’s what made it fascinating to me.

How the Voice Works (Book vs Movie)

Another Bene Gesserit ability is the Voice, what Herbert describes as a kind of audio-neuro control. By precisely modulating pitch and tone based on understanding someone’s psychological state, a trained user can compel obedience.

In the books, it’s described subtly. Paul “adjusted his throat” or “spoke with a tone that brooked no disobedience.” There’s no elaborate explanation of what it sounds like.

The David Lynch film represented it as almost a shout. A command voice like the Thu’um from Skyrim, forceful and unmistakable. During the Gom Jabbar test in that film, when Paul uses the Voice on the Reverend Mother, you hear this resonance. Echoes, a rumble beneath his words. That’s how I started imagining it while reading. Not just louder, but with a quality that reaches into your nervous system and compels you to obey.

For me, it felt like a combination of telekinesis and telepathy channeled through sound. You’re not physically moving someone, but you’re overriding their will through perfectly calibrated vocal manipulation.

Sandworms and Sandwalking

The sandworms of Arrakis, Shai-Hulud, are massive, ancient, territorial. The Fremen worship them as manifestations of God. They ride them using maker hooks that keep segments open, forcing the worm to stay on the surface. The worms are drawn to rhythmic vibrations, so the Fremen practice sandwalking, moving with irregular patterns to avoid detection.

After reading Dune, I became hyperaware of sand and deserts. I’d think about sandwalking. Staying on rocks when possible, avoiding rhythmic movement. It’s completely irrational. There are no sandworms. But that’s what immersive worldbuilding does. It changes how you perceive reality.

It also didn’t help that I’d loved the movie Tremors as a kid. The giant underground worms hunting by vibration. Dune just reinforced that primal fear of what might be lurking beneath loose ground.

Finding Physical Copies: The Book Hunt

I didn’t read these books in neat order. I read them as I found them.

What I Found First (Out of Order)

- Dune. Booksale, 1977 Berkley edition (now lost)

- Children of Dune. Found before Messiah

- Dune Messiah. Found after Children

I read them in proper sequence because reading them out of order would ruin the story. But finding them out of order meant I had to hunt, which made each discovery more meaningful.

The Later Books

- God Emperor of Dune. Couldn’t find a physical copy anywhere. Read it as a PDF

- Heretics of Dune. Also a PDF

- Chapterhouse: Dune. Finally found the newer reprint at National Book Store, but only after I’d already read it digitally

The Prequels

I tracked down the Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson prequels at Fully Booked:

- House Atreides

- House Harkonnen

- House Corrino

These books go back in time to show the origins of the great houses, the political maneuvering that led to the first book’s events, and details about places only mentioned in Herbert’s originals.

The prequels answer questions like: Why are the Harkonnens so twisted? (You see Giedi Prime in detail, the black-sun industrial hellscape where brutality is culture.) Why are the Sardaukar so feared? (You witness their training on Salusa Secundus.) How did the Emperor’s political web get so tangled? (You see the Bene Gesserit breeding program in action, the Guild’s leverage, the complex alliances.)

The prequels don’t have the philosophical density of Herbert’s originals, but they’re solid worldbuilding. For someone like me who wants to understand the source of everything, they mattered. I’ll probably write more about them separately. There’s a lot to unpack there.

Why Physical Books Matter for Collecting

I prefer physical books. Always have.

When I had to read God Emperor and Heretics as PDFs, it worked. I got the story. But it wasn’t the same.

A physical book has weight. You can see your progress. You can flip back to earlier sections without scrolling. You can smell the pages. Yes, I’m one of those people.

And there’s something about the hunt that makes finding a book more meaningful than just clicking “buy now.”

Tracking down the House trilogy at Fully Booked. Finding Chapterhouse at National Book Store after months of looking. Stumbling across that 1977 Berkley edition at Booksale. That was treasure.

Even though that book is gone now, the memory of finding it remains.

That’s part of collecting. Not just owning the books, but the process of searching for them.

If you’re hunting for books yourself, check Booksale, Books for Less, secondhand stores, even the book stalls in Recto. You’d be surprised what you can find if you’re willing to dig.

What Dune Is Really About (Spice, Oil, and Power)

Here’s what most people miss about Dune. It’s not just science fiction. It’s political commentary disguised as space opera.

Spice Isn’t a Drug. It’s Oil.

When I first read Dune, I thought spice was just a sci-fi drug. Something that extends life, enables space travel, grants prescience. Interesting concept.

But the more I read, the more I realized. Spice is oil.

Think about the structure. One desert planet holds the universe’s most valuable resource. Whoever controls that planet controls interstellar commerce and travel. Great powers go to war over access to it. The native population (Fremen) are treated as obstacles by colonial powers who want the resource. The entire political and economic structure of civilization depends on this single commodity from this single location.

Arrakis is the Middle East. The spice trade is the oil economy.

The Fremen aren’t just desert warriors in Herbert’s imagination. They’re clearly inspired by Arab and Bedouin cultures. They’ve lived in that harsh environment for generations while outside imperial powers fight proxy wars over their land for resources they don’t even fully control. Herbert doesn’t hide this. He literally calls Paul’s war across the universe a jihad.

The great houses (Atreides, Harkonnen, Corrino) function like empires and energy corporations fighting over extraction rights and market control.

The Emperor doesn’t want any one house to become too powerful, so he plays them against each other. Classic balance-of-power geopolitics.

The Spacing Guild needs spice to navigate, so they stay politically neutral but hold ultimate economic leverage. Like how global shipping and finance can influence policy without holding direct political power.

This is resource wars. This is colonialism. This is geopolitics.

Herbert wrote this in 1965, but it reads like commentary on every oil conflict since.

Family Atomics and Mutually Assured Destruction

Every great house possesses atomics. Nuclear weapons capable of destroying planets.

But the Great Convention forbids using them against human targets. If any house breaks this taboo, all other houses will unite to destroy the violator.

Sound familiar? That’s mutually assured destruction. The Cold War doctrine that kept nuclear powers from launching because retaliation would annihilate everyone.

Herbert was writing Dune right in the middle of the nuclear arms race. The idea that everyone has civilization-ending weapons but no one can use them without triggering total war isn’t fiction. It’s the reality he lived in.

Paul bends this rule by using atomics against geographical features (blowing a gap in the Shield Wall) rather than directly targeting people. Technically legal. But everyone understands the message. He’s willing to go that far.

That’s brinkmanship. That’s power politics with apocalyptic stakes.

Paul Isn’t a Hero. Leto Isn’t a Villain.

The biggest lesson Dune teaches: beware of messiahs.

Paul becomes a religious figure. Millions die in the jihad waged in his name. He sees the future and is trapped by it. Unable to stop the violence even though he knows it’s coming. His prescience isn’t a gift. It’s a prison.

Leto II takes it further. He transforms into a sandworm-human hybrid and rules as an absolute tyrant for 3,500 years. He’s oppressive, controlling, seemingly monstrous.

But he’s doing it to save humanity from extinction.

This is the Golden Path. Leto sees that humanity is stagnating. Becoming too predictable, too dependent on spice and limited thinking. Without intervention, humanity faces extinction. So he becomes the ultimate oppressor to force humanity to scatter across the universe, evolve, break free of dependence, and survive in forms he’ll never see.

It’s the most twisted form of benevolence in literature.

Herbert isn’t writing about good versus evil. He’s writing about power, control, survival, and the terrible choices people make when they can see consequences others can’t.

Why Dune Deserves Shelf Space

Dune is popular right now because of the films. But Dune has always mattered.

It’s not just a story about a chosen one on a desert planet fighting an evil empire.

It’s about how resource scarcity drives conflict. How environment shapes culture and capability. The danger of hero worship and messianic thinking. Prescience as burden rather than gift. Power structures and how they perpetuate themselves. Human evolution across deep time.

These aren’t simple themes you can absorb in one reading. They require thought, rereading, sitting with uncomfortable ideas.

And that’s what makes the books worth collecting. Not just owning them, but returning to them, discovering new layers each time.

I’ve read all six of Herbert’s books. I’ve read the prequels. I’ve hunted down physical copies when I could, settled for digital when I had to.

Even though my 1977 Berkley edition is gone, the story is still there. The ideas are still there.

And those are worth keeping.